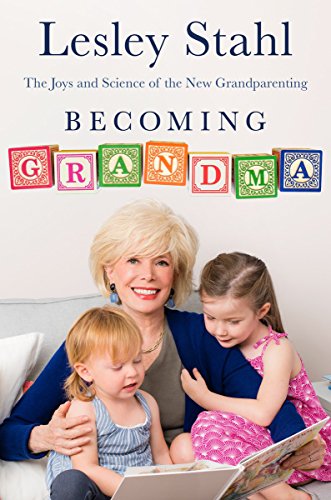

Articles liés à Becoming Grandma: The Joys and Science of the New Grandparen...

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNCopyright © 2016 Lesley Stahl

ONE

Life and Death

It’s never too late to have the best day of your life.

Throughout my career, I worked at suppressing both my opinions and my emotions. I was out on the streets of New York on 9/11 and held myself together. I walked the alleys of Sadr City and once raced to a café in Tel Aviv minutes after it was leveled by a suicide bomber without allowing my fears to surface. I’ve asked embarrassing questions without embarrassment. And I’ve sat opposite mothers of dying children, teenagers who had been abused, and grown men and women who had suffered the indignities of injustice—without breaking down in tears or exploding in outrage. I thought I had become the epitome of self-control.

Then, wham! My first grandchild, Jordan, was born on January 30, 2011. I was jolted, blindsided by a wallop of loving more intense than anything I could remember or had ever imagined.

At the very same time, my mother, Dolly, was dying. It was a disconcerting conjunction, to say the least. Although she had spent the last forty-five years complaining of one illness after the next, it was now for real. She might not live long enough to hold her great-grandchild. In no time my diligently buried emotions burst out like kettle steam.

Dolly had fallen and broken her hip, which set off her rapid decline. My husband, Aaron, and I were with her at the hospital when our daughter, Taylor, called from Los Angeles. All she said was, “They started.” Aaron and I kissed my mother good-bye, assuring her we would call as soon as we knew anything. We drove to her house for our clothes and on to Logan airport to catch the next plane to LAX. Our only child was in labor, four days early.

On the plane I fought off waves of fear: Would the baby be healthy? If something went wrong, would Taylor have to give up her career? For months I’d been pushing away such thoughts, those grandma gremlins. At the same time, I reproached myself for leaving Dolly. Would she be okay until I got back? We hadn’t had the kind of even-keeled relationship I have with Taylor. When Dolly turned ninety-three a few months before, I told her I never thought she’d live that long, and she said: “Well you don’t have to say it so regretfully, ya know.” Her dig, meant to be funny, was a reminder of the old rancor between us. As we both aged and mellowed, we became friends; now it pained me to leave her like that, in the hands of nurses at the hospital.

When we landed, Taylor was back home. She had gone to the hospital too early, and now she and our son-in-law, Andrew Major, were graphing her contractions on an iPad. I was sailing out of body. I couldn’t believe it: my baby—having a baby. How could this be? She was my special Taylor, calm and imperturbable as always. She was signaling that’s what she needed from me. I would have to quiet my nervous excitement.

At five the next morning, Taylor and Andrew raced back to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. By the time Aaron and I got there, Taylor was already in her “birthing room,” which was spacious and light with a panoramic view of the Hollywood Hills. And yes, we could see the sign! Monitoring tubes dangled; a nurse bustled about. Taylor had already been given an epidural, so we would have no Murphy Brown wailing, though I doubt Taylor would’ve wailed even if she’d gone without. Histrionics are simply not on her emotional keyboard.

She seems to have been born with something called hyperthymia. Roughly translated, it means “perpetual happiness.”1 This is one reason we have always had such a good relationship. I have a daughter who didn’t go through the usual teenage miseries or years of hating her mother (I confess to both). We had no melodrama; doors weren’t slammed. She was so even-tempered as a child, I was worried. “It’s just not normal,” I told Aaron. “She must be repressing. Her head’ll blow off one day. She needs to see a child psychiatrist.”

“What’ll you tell him?” he asked. “‘My daughter suffers from being too happy’? Are you kidding?”

Eventually I talked to a shrink myself, who assured me there really are people out there, including teenage girls, who are never moody. Imagine.

So Taylor’s equanimity in the birthing room seemed normal. When the contractions accelerated, it was my stomach that churned: “Where’s the doctor?” I asked the nurse, with an edge. “Why isn’t he here?”

“Oh, we never wake up the doctor early on Sunday,” she explained.

As Taylor lay in bed, uncomfortable but composed, Andrew, Aaron and I followed her cues and forced ourselves into a state of artificial nonchalance. But we are who we are: just as I was about to let loose my pent-up anxiety with a bellowing, “Where the hell is the goddamn doctor?,” in he sauntered, like a reporter meeting a deadline by seconds.

“You’re doing great,” he assured Taylor. “I’ve been monitoring you at home on my iPhone.” Good golly. Look how far we’ve come from house calls. Now doctors treat you from their beds.

He walked Andrew over to the window to show the father-to-be his cool contraction app. They chatted and swapped other new apps like two friends in a bar until Taylor said: “Hey, fellas, over here. Isn’t this my show?”

Fifteen minutes later, the doctor announced: “Showtime!” And asked, “Will your parents stay?”

To my disappointment, Taylor said no. So Aaron and I slouched off to the empty waiting room. It seems that many of the births at Cedars-Sinai are Caesarean, by appointment, something Taylor was offered but passed on. Doctors like their Sundays off. As far as we could tell, only one other baby was born in the hospital that morning.

We paced and twitched and checked our watches every three minutes like actors before the curtain. Aaron and I already knew that it was a girl, and that her name would be Jordan, a name beginning with J after my brother, Jeff (who died in September 1999). I’d gone with Taylor to several doctor appointments, had heard the astoundingly strong heartbeat at just ten weeks, and at three months I’d watched little arms and legs float and wiggle on the ultrasound screen.

We weren’t in the waiting room very long before the doctor appeared. “The baby’s perfect,” he told us. “Out in less than forty minutes. An easy birth as these things go.”

We ran back to the birthing room to see Jordan for the first time, swaddled in Taylor’s arms, a little bundle weighing six pounds, fourteen ounces. I thought: A whole new person, and she’s mine. I was so pumped, my heart was on a trampoline. And there was my daughter, soft in a way I’d never seen. Was this my tomboy who wouldn’t wear dresses? She was now a Giotto Madonna.

Andrew was stretched out on the bed next to her so they could pass the baby back and forth. A pair so suddenly a three- some. At one point Andrew took Tay’s face in his hands and kissed her lips twenty times.

Andrew has a temperament as steady and unflappable as Taylor’s. They had met when he was working for Rob Lowe on The West Wing and she was a production assistant at a small movie company called Middle Fork. Her boss asked her to hire a new assistant. Andrew applied. Taylor loved his looks—he’s often mistaken for Tobey Maguire—and she thought he was funny, which he is. She especially loved that he could tell stories about The West Wing, her favorite television show. She hired him on the spot.

A few years later he found a better job as a television writer in New York. Taylor told him it was okay with her as long as he moved in with Aaron and me, which he did, living with us in our small apartment for more than a year. The first few weeks were inevitably awkward. When Aaron and I had plans for dinner out, for example, we would call Tay in LA to see if Andrew wanted to join us. She’d call him in his bedroom, which was next to Aaron’s office, where we were waiting for an answer. She’d call us back. “Yup, he’d love to.”

The crazy three-step communication system (we didn’t want him to have to say no to our faces) didn’t last long. Within a few weeks Aaron and I were feeling we had reconstituted our family with an only child. Well, almost reconstituted. I’ve discovered that no matter how warm the relationship, there’s always a certain etiquette when you deal with an in-law, a trace of formality.

On the day of Jordan’s birth, I loved him like a son. Everything was unceremonious and comfortable. Since he and Tay had come to the hospital early, I kept urging them to take a nap. They laughed and teased me—I guess it was pretty obvious that all I wanted was to hold Jordan. Have her to myself. I thought about what one of my friends who had just become a grandmother told me: “All I wanted to do was lick the baby’s face!”

When it was finally my turn, I felt I was growing a whole new chamber in my heart. I nearly swooned, staring at her like a lover. I’d never seen anything so delicate and beautiful, so sweet, every feature perfect. And it’s not that I didn’t see her three chins.

This is what I didn’t expect. I was at a time in my life where I assumed I had already had my best day, my tallest high. But now I was overwhelmed with euphoria. Why was she hitting with such a force? What explains this enormous joy, this grandmother elation that is a new kind of love?

At first I wondered if it was from seeing my child become a mother. Or maybe I was subliminally realizing the forwarding of my bloodline, that my DNA had transferred to the new generation. Was I hearing little cries of joy from my genes—“I am fulfilled!”?

One friend told me that what struck her was that the seed of her grandchild was already in her daughter’s body when the daughter was a fetus in her body. What an extraordinary thought, Jordan developing in Taylor when she was in my womb.

All I knew for sure was that I was in unknown territory. This was very different from the day Taylor was born. Hers had been a Caesarean birth, so for several days I was a woozy patient on serious drugs. It was Aaron who changed her diapers, wrapped her up in blankets, and walked her around the room. Now, as a grandmother, I was in perfect health, clearheaded, and not at all pleased whenever Aaron asked for his turn. What, hand her over?

When I did, reluctantly, Aaron held his granddaughter in the palm of one hand. This Texas-tall 230-pounder began muttering soft baby talk. I decided it was a good time to call my mother, still in the hospital three thousand miles away.

“Jordan’s here! And she’s perfect!”

But Dolly yelled at me, snapping me into a different reality. “Get me out,” my mother demanded. “They don’t do anything for me here.”

“What do you need?” I asked.

“I want to turn to face the door.” But turning would put her on her bad hip. I felt so helpless. I tried again: “Dolly, you have a great-granddaughter.” But she just continued to chastise me for leaving her. This was a dark shadow on the day. My mother was unable to appreciate what she had so long yearned for.

Dolly had not wanted to be a grandmother. She thought it would mark her as old. But by eighty-five, she’d become what none of us ever foresaw: a sweet little old lady (for most of the time). With her transformation came a craving for a great-grand- child. She wanted it so badly, she once hung up on Taylor when she had to admit: “No, Dolly, I’m not pregnant yet.”

I, on the other hand, wanted to be a grandmother from the age of forty-five—when Tay was only ten. The tug for a grand- child was real and persistent. It made the arrival all the sweeter.

An hour after the birth, Taylor and Jordan were moved into a cramped single room overlooking a concrete wall. Jordan slept at the foot of Tay’s bed, a collapsing pink balloon tied to her plastic bassinet.

Thinking up a name for her had been an ordeal. It actually started with a disagreement over a name for Taylor and Andrew’s puppy. Aaron proposed Gilley; I was pushing Gertrude. But they wanted a strong unisex name and finally settled on Sydney.

When it came to my grandchild, the process was a long wrestle. “I love the name Violet,” I said.

“I hate flower names,” said Taylor.

Aaron switched to cities: “Paris?”

“Paris Hilton. No way.”

Aaron tried again. “Dallas.”

“Dallas Major? Come on. It sounds like a stripper.”

My turn: “I have a wonderful friend named Vijay. I love that.”

“They’d call her Vagina.”

I proposed BJ. “She’d be Blow Job.”

Wisely, Taylor kept their choice secret until three days before she delivered.

Then there was the issue of what Jordan would call us. I told Taylor I’d like to be “Granny.”

“No way” was her reaction. “It sounds frumpy.”

I still liked it but was told that no matter what I decreed, the baby would call me whatever she called me. I thought that was nonsense. My mother wanted to be called Dolly, and all her grandchildren complied.

What if the baby tried to say my name? How would Lesley come out? Then it came to me: Lolly! It would come out Lolly— if I told her so. So I would be Lolly, and Aaron would be Pop. That’s what he called his dad. We would be LollyPop. Cute, huh? Both Jordan and I had new names.

As a grandmother for only a few hours, I was enveloped in newness. I supposed I shouldn’t have been, but I was startled when a lactation specialist dropped by. “Taylor, you’re going to breast-feed? Really?” This was something neither I nor most of my friends even considered. We were in the first wave of women invited into the workplace under the banner of affirmative action, thinking we had to prove we could do our jobs as well as—and just like—the men. They didn’t breast-feed; we didn’t breast-feed.

With Taylor and her friends, it’s a given. She had taken a class on it, but now, on her first try, she said, “I forget everything. Neither Jordan nor I know what to do.” I was of no help. It did cross my mind: Thank God I didn’t put myself through this.

The second feeding went a little better, though Taylor told me: “It doesn’t feel good at all.” She was supposed to nurse twenty minutes on each side, but it took ninety minutes since Jordan wasn’t getting the hang of it, and Tay was wincing with pain. “She’s given me a hickey already.”

Jordan began to cry. “So sad,” said Tay. “She probably hasn’t had anything to eat at all.”

Unlike tiger cubs, our babies are feeding incompetents in need of aggressive tutoring. The lactation nurse drizzled formula on the nipple to spark Jordan’s appetite. That’s when I congratulated my- self once again for abstaining. I would’ve been a nervous wreck, which the baby would surely have felt and internalized. Ha! I thought. Taylor is calm and centered because I used a bottle!

I called Dolly again; her nurse told me she wasn’t eating either.

On day two Taylor was in major pain and deeply worried about her baby getting nourishment. When she asked to spend another night in the hospital, I said good idea. The baby nurse wasn’t coming for four more days, and Andrew was exhausted. When Dr. Laid-Back ambled in and slumped in the chair, Taylor complained that she couldn’t get herself up and out of bed. She didn’t tell him how inadequate she felt about the breast-feeding. In any case, the doctor said...

—Judy Woodruff, PBS Newshour

“[Stahl] turns her gaze inwards on the experience of being a grandmother . . . If every grandparent out there will buy this book they will be rewarded.”

—Charlie Rose, Charlie Rose

“It’s the personal stories that make [Becoming Grandma] so accessible... In the most illuminating parts of her book, Stahl writes candidly about her own experiences as a mother, wife, reporter and now, grandmother.”

—The Richmond Times-Dispatch

“[An] energetic, informative, and often touching book....Stahl includes stories of generational conflict [and] plentiful glimpses of her family’s joys and those of many others...No matter where readers fall in age or experience, this book should top their 2016 reading list of parenting titles.”

—Publishers Weekly, STARRED REVIEW

“An ode to mimis, bubbes and nanas everywhere . . . Lesley Stahl reports from the fascinating front lines of modern grandparenting.”

—Pamela Druckerman, author of Bringing Up Bébé

“Lesley Stahl brings the keen reporting we know from “60 Minutes” to the story of grandparenting. Amazed and delighted at the joy she experienced with the arrival of own two granddaughters, Stahl set about finding out why that was true. Her wise answers, both scientific and practical, provide useful information not only for grandparents and the children they cherish, but also for the wider society. This is a wonderfully fun read about an important subject.”

—Cokie Roberts, author of We Are Our Mothers’ Daughters

“Lesley Stahl, one of America's most well-respected journalists, uses her reporter's instinct and grandmother's heart to take a bold look at life's most joyful relationship in Becoming Grandma. Stahl's wisdom, experience, and boundless love for her own granddaughters bring stunning new insights into this classic bond. I loved this book—a must-read for every family.”

—Linda Fairstein, author of Devil’s Bridge

“Award-winning broadcast journalist Stahl [investigates] the importance of the role grandparents can play in the lives of their children and grandchildren....Through the medium of her own experiences, the author delivers a wise and witty book. A welcome guide for new grandparents and their children looking to savor the joys and navigate the pitfalls of grandparenting.”

—Kirkus

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurThorndike Pr

- Date d'édition2016

- ISBN 10 1410487911

- ISBN 13 9781410487919

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages371

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 3,68

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Becoming Grandma (Thorndike Press Large Print Popular and Narrative Nonfiction)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_1410487911

Becoming Grandma (Thorndike Press Large Print Popular and Narrative Nonfiction)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard1410487911

Becoming Grandma (Thorndike Press Large Print Popular and Narrative Nonfiction)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think1410487911

Becoming Grandma (Thorndike Press Large Print Popular and Narrative Nonfiction)

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover1410487911

Becoming Grandma (Thorndike Press Large Print Popular and Narrative Nonfiction)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. Brand New!. N° de réf. du vendeur VIB1410487911

Becoming Grandma (Thorndike Press Large Print Popular and Narrative Nonfiction)

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new1410487911