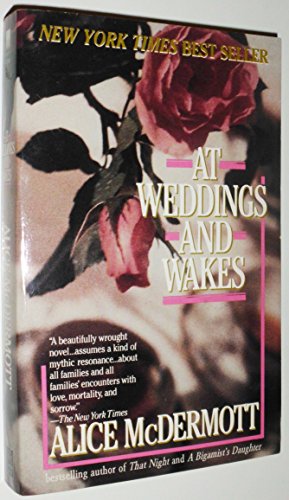

Articles liés à At Weddings and Wakes

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNBook by McDermott Alice

Les informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

Extrait :

1

TWICE A WEEK in every week of summer except the last in July and the first in August, their mother shut the front door, the white, eight-panel door that served as backdrop for every Easter, First Holy Communion, confirmation, and graduation photo in the family album, and with the flimsy screen leaning against her shoulder turned the key in the black lock, gripped the curve of the elaborate wrought-iron handle that had been sculpted to resemble a black vine curled into a question mark, and in what seemed a brief but accurate imitation of a desperate housebreaker, wrung the door on its hinges until, well satisfied, she turned, slipped away from the screen as if she were throwing a cloak from her shoulders, and said, "Let's go."

Down the steps the three children went before her (the screen door behind them easing itself closed with what sounded like three short, sorrowful expirations of breath), the two girls in summer dresses and white sandals, the boy in long khaki pants and a thin white shirt, button-down collar and short sleeves. She herself wore a cotton shirtwaist and short white gloves and heels that clicked against the concrete of the driveway and the sidewalk and sent word across the damp morning lawns that the Daileys (Lucy and the three children) were once again on their way to the city.

The neighborhood at this hour was still and fresh and full of birdsong and the children marked the ten shady blocks to the bus with three landmarks. The first was the ragged hedge of the Lynches' corner lot where lived, in a dirty house made ramshackle by four separate, slapdash additions, ten children, three grandparents, a mother, a father, and a bachelor uncle who was responsible, no doubt, for the shattered brown bottle that lay on the edge of the driveway. The second was a slate path that intersected a neat green lawn, each piece of slate the exact smooth color, either lavender or gray or pale yellow, of a Necco candy wafer. Third was the steel eight-foot fence at the edge of the paved playground of the school they had all attended until June and would attend again in September, although it appeared to them as they passed it now as something forlorn and defeated, something that the wind might take away—something that could rumble with footsteps and shriek with bells and hold them in its belly for six hours each day only in the wildest, the most terrible, the most unimaginable (and, indeed, not one of the three even imagined it as they passed) of dreams.

At the bus stop, the tall white sign with its odd, flat, perforated pole drew them like magnets. They touched it, towing the pebbles at its base. They jumped up to slap its face. They held it in one hand and leaned out into the road looking for the first glint of sun against the white crown and wide black windshield of the bus that would take them to the avenue.

Their mother smoked a cigarette on the sidewalk behind them, as she did on each of these mornings, her pocketbook hung in the crook of her arm, the white gloves she would pull on as soon as the bus appeared squeezed together in her free hand. The sun at nine-fifteen had already begun to push its heat through the soles of her stockings and beneath the fabric-covered cardboard of her belt. She touched the silver metal of its buckle, breathed in to gain a moment's space between fabric and flesh. Across the street a deli and a bar and a podiatrist's office shared a squat brick building that was shaded by trees. Beyond it a steeple rose—the gray steeple of the Presbyterian church—into a sky that was blue and cloudless. Swinging from the bus-stop sign, the children failed to imagine for their mother, just as they had failed to imagine for the building where they went to school, any other life but the still and predictable one she presented on those mornings, although even as she dropped her cigarette to her side and stepped on the butt with her first step toward them (it was a woman's subtle, sneaky way of finishing a smoke) she was aware of the stunned hopelessness with which she moved. Of time draining itself from the scene in a slow leak.

Briefly terrified, the younger girl took her mother's hand as the bus wheezed toward the curb.

Even the swift, gritty breeze that rushed through the slices of open window seemed at this hour to be losing the freshness of morning—some cool air clung to it, but in patches and tatters, as if the coming heat of the afternoon had already begun to wear through.

The children squinted their eyes against it and shook back their hair. Watching the houses go by, they were grateful that theirs was not one of them to be left, after each stop, in the expelled gray exhaust, and as the bus moved past the cemetery they felt—all unconsciously—the eternal disappointment of the people whose markers lay so near the road. Who saw (because they imagined the dead to be at eye level with the ground, the grass pulled like a blanket up to their noses) the walking living through the black stakes of the iron fence and the filtered refuse of what seemed many summers—ice-cream wrappers, soda cans, cigarette butts, and yellowed athletic socks—that had gathered at its base.

Where the cemetery ended, the stonecutter's yard began, a jumble of unmarked and broken tombstones that parodied the order of the real graves and seemed in its chaos to indicate a backlog of orders, a hectic rate of demand. (Their father's joke, no matter how many times they drove this way: "People are dying to get in there.") Then, at the entrance to the yard, a showroom—it looked for all the world like a car showroom—that displayed behind its tall plate glass huge marble monuments and elaborate crypts and the slithering reflected body of their bus, their own white faces at three windows.

They passed another church, a synagogue, and then a last ramshackle yard where chickens pecked at the dirt in speckled sunlight and what the children understood to be a contraption in which wine was made (although they couldn't say how they knew this) hulked among the vines and the shadows, through which they also glimpsed, passing by, a toothless Italian man named (and they could not say how they knew this, either) Mr. Hootchie-Koo, as he shuffled through the dirt in baggy pants and bedroom slippers.

Now the large suburban trees fell away. There was another church and then on both sides of the road a wide expanse of shadeless parking lot, the backs of stores, traffic. Their mother raised her hand to pull the cord that rang the buzzer and then waited in the aisle for them to go before her toward the front, hand over hand like experienced seamen between the silver edges of the seats. Their first sight as they touched the ground was always the identical Chinese couple in the narrow laundry, looking up through the glass door from their eternal white and pale blue pile.

As they stood on the corner the bus they had just deserted, suddenly grown taller and louder and far more dangerous, passed before their noses, spilling its heat on their thin shoes.

When the light changed they crossed. Here the sidewalk was wider, twice as wide as it was where they lived, and they began to catch a whiff, a sense, of their destination, the way some sailors, hundreds of miles out, are said to catch the first scent of land. There was a bar—a saloon was how the children thought of it—with a stuccoed front and a single mysterious brown window, a rounded doorway like the entrance to a cave that breathed a sharp and darkly shining breath upon them, a distallation of night and starlight and Scotch. Two black men passed by. In a dark and narrow candy store that smelled exotically of newsprint and bubble gum they were each allowed to choose one comic book from the wooden rack and their mother gathered these in her gloved hand, placed them, a copy of the Daily News, and a pack of butterscotch Life Savers on the narrow shelf beside the register, and paid with a single bill.

Outside, she redistributed the comics and placed a piece of candy on each tongue, fortifying the children, or so it seemed, for the next half of their journey. She herded them into the shaded entry of a clothing store, another cave formed by two deep windows that paralleled each other and contained, it seemed, a single example of every item sold by the store, most of which was worn by pale mannequins with painted hair and chipped fingers or mere pieces of mannequins: head, torso, foot. The store was closed at this hour and the aisles were lined with piles of thin gray cardboard boxes that sank into one another and overflowed with navy-blue socks or white underpants as if these items had somehow multiplied themselves throughout the night.

When the bus appeared it was as if from the next storefront and they ran across the wide sidewalk to meet it, their mother pausing behind them to step on another cigarette. She offered the driver the four slim transfers while the children picked their way down the aisle. There was not the luxury of empty seats there had been on the first bus and so they squeezed together three to a narrow seat, their mother standing in the aisle beside them, her dress, her substantial thigh and belly underneath blue-and-white cotton, blocking them, shielding them, all unaware, from the drunks and the gamblers and the various tardy (and so clearly dissipated) businessmen who rode this bus though never the first because this was the one that both passed the racetrack and crossed the city line.

All unaware, noses in their comics, her three children leaned together in what might have been her shadow, had the light been right, but was in reality merely the length that the warmth of her body and the odor of her talc extended.

At the subway, the very breath of their destination rose to meet them in the constant underground breeze that began to whip the girls' dresses as soon as they descended the first of the long set of dirty stairs. ("No spitting" a sign above their heads read, proving to them that they were ente...

Revue de presse :

TWICE A WEEK in every week of summer except the last in July and the first in August, their mother shut the front door, the white, eight-panel door that served as backdrop for every Easter, First Holy Communion, confirmation, and graduation photo in the family album, and with the flimsy screen leaning against her shoulder turned the key in the black lock, gripped the curve of the elaborate wrought-iron handle that had been sculpted to resemble a black vine curled into a question mark, and in what seemed a brief but accurate imitation of a desperate housebreaker, wrung the door on its hinges until, well satisfied, she turned, slipped away from the screen as if she were throwing a cloak from her shoulders, and said, "Let's go."

Down the steps the three children went before her (the screen door behind them easing itself closed with what sounded like three short, sorrowful expirations of breath), the two girls in summer dresses and white sandals, the boy in long khaki pants and a thin white shirt, button-down collar and short sleeves. She herself wore a cotton shirtwaist and short white gloves and heels that clicked against the concrete of the driveway and the sidewalk and sent word across the damp morning lawns that the Daileys (Lucy and the three children) were once again on their way to the city.

The neighborhood at this hour was still and fresh and full of birdsong and the children marked the ten shady blocks to the bus with three landmarks. The first was the ragged hedge of the Lynches' corner lot where lived, in a dirty house made ramshackle by four separate, slapdash additions, ten children, three grandparents, a mother, a father, and a bachelor uncle who was responsible, no doubt, for the shattered brown bottle that lay on the edge of the driveway. The second was a slate path that intersected a neat green lawn, each piece of slate the exact smooth color, either lavender or gray or pale yellow, of a Necco candy wafer. Third was the steel eight-foot fence at the edge of the paved playground of the school they had all attended until June and would attend again in September, although it appeared to them as they passed it now as something forlorn and defeated, something that the wind might take away—something that could rumble with footsteps and shriek with bells and hold them in its belly for six hours each day only in the wildest, the most terrible, the most unimaginable (and, indeed, not one of the three even imagined it as they passed) of dreams.

At the bus stop, the tall white sign with its odd, flat, perforated pole drew them like magnets. They touched it, towing the pebbles at its base. They jumped up to slap its face. They held it in one hand and leaned out into the road looking for the first glint of sun against the white crown and wide black windshield of the bus that would take them to the avenue.

Their mother smoked a cigarette on the sidewalk behind them, as she did on each of these mornings, her pocketbook hung in the crook of her arm, the white gloves she would pull on as soon as the bus appeared squeezed together in her free hand. The sun at nine-fifteen had already begun to push its heat through the soles of her stockings and beneath the fabric-covered cardboard of her belt. She touched the silver metal of its buckle, breathed in to gain a moment's space between fabric and flesh. Across the street a deli and a bar and a podiatrist's office shared a squat brick building that was shaded by trees. Beyond it a steeple rose—the gray steeple of the Presbyterian church—into a sky that was blue and cloudless. Swinging from the bus-stop sign, the children failed to imagine for their mother, just as they had failed to imagine for the building where they went to school, any other life but the still and predictable one she presented on those mornings, although even as she dropped her cigarette to her side and stepped on the butt with her first step toward them (it was a woman's subtle, sneaky way of finishing a smoke) she was aware of the stunned hopelessness with which she moved. Of time draining itself from the scene in a slow leak.

Briefly terrified, the younger girl took her mother's hand as the bus wheezed toward the curb.

Even the swift, gritty breeze that rushed through the slices of open window seemed at this hour to be losing the freshness of morning—some cool air clung to it, but in patches and tatters, as if the coming heat of the afternoon had already begun to wear through.

The children squinted their eyes against it and shook back their hair. Watching the houses go by, they were grateful that theirs was not one of them to be left, after each stop, in the expelled gray exhaust, and as the bus moved past the cemetery they felt—all unconsciously—the eternal disappointment of the people whose markers lay so near the road. Who saw (because they imagined the dead to be at eye level with the ground, the grass pulled like a blanket up to their noses) the walking living through the black stakes of the iron fence and the filtered refuse of what seemed many summers—ice-cream wrappers, soda cans, cigarette butts, and yellowed athletic socks—that had gathered at its base.

Where the cemetery ended, the stonecutter's yard began, a jumble of unmarked and broken tombstones that parodied the order of the real graves and seemed in its chaos to indicate a backlog of orders, a hectic rate of demand. (Their father's joke, no matter how many times they drove this way: "People are dying to get in there.") Then, at the entrance to the yard, a showroom—it looked for all the world like a car showroom—that displayed behind its tall plate glass huge marble monuments and elaborate crypts and the slithering reflected body of their bus, their own white faces at three windows.

They passed another church, a synagogue, and then a last ramshackle yard where chickens pecked at the dirt in speckled sunlight and what the children understood to be a contraption in which wine was made (although they couldn't say how they knew this) hulked among the vines and the shadows, through which they also glimpsed, passing by, a toothless Italian man named (and they could not say how they knew this, either) Mr. Hootchie-Koo, as he shuffled through the dirt in baggy pants and bedroom slippers.

Now the large suburban trees fell away. There was another church and then on both sides of the road a wide expanse of shadeless parking lot, the backs of stores, traffic. Their mother raised her hand to pull the cord that rang the buzzer and then waited in the aisle for them to go before her toward the front, hand over hand like experienced seamen between the silver edges of the seats. Their first sight as they touched the ground was always the identical Chinese couple in the narrow laundry, looking up through the glass door from their eternal white and pale blue pile.

As they stood on the corner the bus they had just deserted, suddenly grown taller and louder and far more dangerous, passed before their noses, spilling its heat on their thin shoes.

When the light changed they crossed. Here the sidewalk was wider, twice as wide as it was where they lived, and they began to catch a whiff, a sense, of their destination, the way some sailors, hundreds of miles out, are said to catch the first scent of land. There was a bar—a saloon was how the children thought of it—with a stuccoed front and a single mysterious brown window, a rounded doorway like the entrance to a cave that breathed a sharp and darkly shining breath upon them, a distallation of night and starlight and Scotch. Two black men passed by. In a dark and narrow candy store that smelled exotically of newsprint and bubble gum they were each allowed to choose one comic book from the wooden rack and their mother gathered these in her gloved hand, placed them, a copy of the Daily News, and a pack of butterscotch Life Savers on the narrow shelf beside the register, and paid with a single bill.

Outside, she redistributed the comics and placed a piece of candy on each tongue, fortifying the children, or so it seemed, for the next half of their journey. She herded them into the shaded entry of a clothing store, another cave formed by two deep windows that paralleled each other and contained, it seemed, a single example of every item sold by the store, most of which was worn by pale mannequins with painted hair and chipped fingers or mere pieces of mannequins: head, torso, foot. The store was closed at this hour and the aisles were lined with piles of thin gray cardboard boxes that sank into one another and overflowed with navy-blue socks or white underpants as if these items had somehow multiplied themselves throughout the night.

When the bus appeared it was as if from the next storefront and they ran across the wide sidewalk to meet it, their mother pausing behind them to step on another cigarette. She offered the driver the four slim transfers while the children picked their way down the aisle. There was not the luxury of empty seats there had been on the first bus and so they squeezed together three to a narrow seat, their mother standing in the aisle beside them, her dress, her substantial thigh and belly underneath blue-and-white cotton, blocking them, shielding them, all unaware, from the drunks and the gamblers and the various tardy (and so clearly dissipated) businessmen who rode this bus though never the first because this was the one that both passed the racetrack and crossed the city line.

All unaware, noses in their comics, her three children leaned together in what might have been her shadow, had the light been right, but was in reality merely the length that the warmth of her body and the odor of her talc extended.

At the subway, the very breath of their destination rose to meet them in the constant underground breeze that began to whip the girls' dresses as soon as they descended the first of the long set of dirty stairs. ("No spitting" a sign above their heads read, proving to them that they were ente...

"A haunted, troubled, beautifully articulated journey into the past."--San Francisco Chronicle.

"It's hard to lift your eyes at the end of the book... you'll find yourself reading every word of Alice McDermott's new novel, not because it's complicated but because such wonderful things happen deep inside the sentences."--Newsweek.

"A brilliant, highly complex, extraordinary piece of fiction and a triumph for its author."--Chicago Tribune.

"A haunting and masterly work of literary art."--The Wall Street Journal

"It's hard to lift your eyes at the end of the book... you'll find yourself reading every word of Alice McDermott's new novel, not because it's complicated but because such wonderful things happen deep inside the sentences."--Newsweek.

"A brilliant, highly complex, extraordinary piece of fiction and a triumph for its author."--Chicago Tribune.

"A haunting and masterly work of literary art."--The Wall Street Journal

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurWarner Books

- Date d'édition1993

- ISBN 10 0440215234

- ISBN 13 9780440215233

- ReliureBroché

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

EUR 14,15

Frais de port :

EUR 5,01

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

At Weddings and Wakes McDermott, Alice

Edité par

Dell

(1993)

ISBN 10 : 0440215234

ISBN 13 : 9780440215233

Neuf

Mass Market Paperback

Quantité disponible : 1

Vendeur :

Evaluation vendeur

Description du livre Mass Market Paperback. Etat : New. In shrink wrap. N° de réf. du vendeur 10-12588

Acheter neuf

EUR 14,15

Autre devise