Articles liés à Fraternity: In 1968, a Visionary Priest Recruited 20...

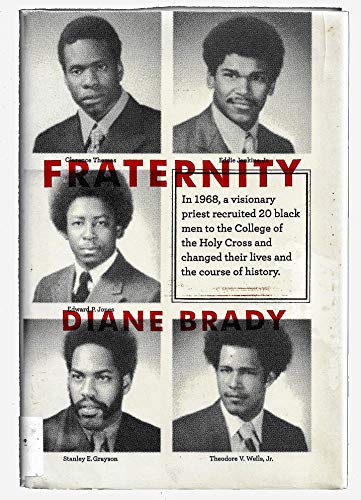

Fraternity: In 1968, a Visionary Priest Recruited 20 Black Men to the College of the Holy Cross and Changed Their Lives and the Course of History. - Couverture rigide

L'édition de cet ISBN n'est malheureusement plus disponible.

Afficher les exemplaires de cette édition ISBNLes informations fournies dans la section « Synopsis » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

All of King’s Men

On April 4, 1968, eight black students were enrolled at the College of the Holy Cross. One, an outgoing and opinionated sophomore named Arthur “Art” Martin, from Newark, New Jersey, was studying in his dorm’s common room when he heard a commotion in the hall. A white student ran in and announced to everyone present that “Martin Luther Coon” had been shot. He looked Art straight in the eye, as if daring him to acknowledge the slur. There was an uncomfortable silence in the room as the other students all turned to stare, curious to see how the black student was going to react to the news of the civil rights leader’s death. Art calmly got up and left the study area. He held his composure until he found his friend Orion Douglass, a black senior from Savannah, and only then did his tears start to flow.

About 1,400 miles away, at the Immaculate Conception Seminary, a young student was battling his rage. Conception, Missouri, was no place to mourn the death of a black man. Clarence Thomas knew he didn’t fit in. From the minute he had arrived from Georgia in the tiny rural community where he had come to study for the priesthood, he’d had misgivings that were increasingly hard to ignore. Thomas had promised his grandfather that he would become the first black priest in Savannah, and he knew that the consequences of letting down the man who had raised him would be dire. His grandfather had made it clear that if Thomas dropped out of school, he would not be welcome back home. Thomas hadn’t expected to have fun in Missouri—he wasn’t the type of teenager who put having a good time ahead of an education—but the isolation and loneliness he experienced was a shock. While Thomas may have come across as friendly and enthusiastic to his fellow seminarians—three of whom were black—he had privately come to loathe his life at the pastoral theology school. Though he liked quite a few of his peers, he felt he had little in common with them. They sometimes stared at his black skin and spoke disparagingly about men like Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. The biggest problem, though, wasn’t the other men but the demons he was battling within himself. Thomas had been mourning the death of a friend who had been killed in a fight in Savannah, and had been reading about the philosophies of a new generation of black leaders.

That sorrow, combined with the racial tensions he felt at the seminary, had merely added to his doubts about why he was there. The Roman Catholic Church had once seemed like a sanctuary from racism to Thomas. The Franciscan sisters who had taught him at St. Benedict the Moor Grammar School had shown him a level of respect he had rarely encountered on the streets of Savannah. Even St. John Vianney Minor Seminary, a white boarding school near Savannah where he had finished up high school and endured occasional teasing, had been at least tolerable in his mind. But a lot had changed over the past year. Civil rights activists like Stokeley Carmichael and Bobby Seale had helped to make black power a rallying cry on campuses nationwide, instilling black students with both a sense of pride and anger about social injustice. There was a growing sense across the country that it was time to give African Americans the rights they had been denied for so long. But one institution that had yet to come to that conclusion, in Thomas’s view, was the Roman Catholic Church. Despite the bold and inclusive vision of Catholicism that emerged from the Second Vatican Council, or Vatican II, he saw hypocrisy in where the Church was spending its energies. Thomas found that the Church’s discussions about how to become more relevant were lacking any real focus on the evils of racism, or on the racial segregation within the Church hierarchy. Thomas had once believed that becoming a priest would put him on equal footing with his white peers; now he wasn’t so sure. With each passing day, he instead felt more diminished and full of doubt.

Even as he gave the appearance of fitting in, Thomas felt left out by the conversations that seemed to grow quieter when he entered a room, the choice of TV shows in common areas, and even the letters that other students received from parents who seemed to care about their sons in a way that his own mother and father never had. His father had left the family when Clarence was a toddler, while his mother had left her two boys with their grandfather when Thomas was barely seven.

The scripture Thomas studied felt out of sync with the realities of 1968. The men living in Conception seemed to him oblivious to a world that was exploding with images of war, protests, and injustice. Instead of acting as a catalyst in the push for racial equality, the Church seemed to have become an oasis from it. It was hard for him to keep his faith when, amid all the battles and debates and violence over civil rights, the Church said nothing. As he would say years later, the silence haunted him.

Martin Luther King, Jr., was a beacon of hope for Thomas; through his work, King had helped him to articulate the pain he felt at being black in a racist world, a pain that Thomas had worked hard to ignore most of his life. The only time he had really been unaware of it was in the small black community of Pin Point, Georgia, where he had lived until the age of six. After his younger brother, Myers, accidentally burned down the house where they lived, the boys had moved to the slums of Savannah with their mother while Thomas’s older sister stayed in Pin Point with another relative.

On the evening of April 4, Thomas was walking back to his dormitory when one of the men watching TV suddenly yelled that King had been shot. As Thomas stood there, trying to digest the news, he heard a white classmate say, “That’s good. I hope the son of a bitch dies.” The man who’d said he hoped King would die was a future priest. In that moment, all of the white students seemed the same to Thomas. Just as King had given voice to Thomas’s hopes, one wisecracking student brought clarity to his anger. It was apparent to him that he didn’t belong with these men. There was no sanctuary in the Church, no equality in Catholicism for people like him. Thomas no longer felt a desire to swallow his rage and head off to the chapel to pray. He simply made a decision, then and there, to leave the seminary and never come back. Later in life, Thomas would refer back to King’s death as a turning point, as the moment when he abandoned both his faith and his vocation.

At eighteen, Eddie Jenkins had a confidence that many adults envied. He was handsome, in an approachable sort of way, and had a reputation for being charming and funny. His days were filled with commuting more than two hours to school and football practice in Brooklyn before returning to Queens and his after-school job at Alexander’s department store. On April 4, Jenkins was stocking shelves at Alexander’s when he looked up to see an older black man walking slowly toward him. What an Uncle Tom, the teen thought to himself. The low hang of the stranger’s head gave the man the kind of look that men his father’s age sometimes had, as if they had spent so much of their lives bowing to white people that they had forgotten how to stand tall. Jenkins turned away in disgust and went back to his work, absently wondering why the street outside wasn’t buzzing with its usual mix of music, laughter, and the chatter of commuters.

As the man approached him, Jenkins grudgingly asked if he needed help.

“The king is dead,” the man said.

Jenkins saw tears in the man’s eyes and suddenly understood why he looked so beaten down. Martin Luther King, Jr., was dead. The teen was overcome with shock. But his most overwhelming reaction was shame—shame that he had stereotyped a grieving man as a coward.

The man looked straight into Jenkins’s eyes. “You can go home now,” he said. The statement struck him as surprisingly bold, but Jenkins immediately went to the register and cashed out. When he turned around, the man was gone. Once outside, he realized again how quiet the streets were. In other parts of the city, people were already smashing store windows and setting fires, but on Queens Boulevard it seemed like the world had stopped. The few people who were still milling around were walking in silence, trying to absorb King’s death. When Jenkins got home to the Flushing section of Queens known as “Da’Ville,” his family was gathered in the living room.

“It had to be a white man,” his father said, looking up from the TV. Eddie’s father was a former merchant marine with a strong gut instinct. It was a trait that had enabled him to form the neighborhood’s first boys’ baseball team when Eddie was eight, soliciting hand-me-down uniforms from the local Jewish league and inviting white boys who hadn’t made the cut elsewhere. The team won the league championships in its first year, and Jenkins’s father went on to become league commissioner. No one knew yet who had killed King, but there was no doubt in Eddie’s father’s voice. Moreover, everyone else in the room was equally convinced that he was right.

At that moment, all of the speeches Eddie had heard from his father about learning to work with white people felt meaningless. The world was divided again. Eddie thought there was no way that black America would let this man die without some kind of retribution. He wanted to rush outside to see what was happening, but his parents convinced him to stay in the house. He had too much to lose, they said—the chance at a football scholarship, college, a lucrative career. None of those things would come to someone who was caught participating in violent demonstrations. Eddie obediently sat down in the living room and stared numbly at the TV.

Years later, after Jenkins and his Miami Dolphins had won the 1973 Super Bowl and he had moved from the NFL to become a politically active lawyer and chairman of the Massachusetts Alcoholic Beverages Control Commission, he would still cite King’s death as a turning point in his life. The civil rights battles that had seemed somewhat abstract up to that point suddenly felt personal.

By the age of seventeen, Edward Paul Jones had given up on the idea of real friendship. He and his family had already moved eighteen times around their poor northwest neighborhood in Washington, D.C. What had stayed consistent, he would later recall, were the rats and rent collectors that seemed to follow them to each new location. On the night of April 4, Jones was where he usually was at that time of day, at home, sitting alone and reading a book.

His mother was washing dishes, cleaning floors, and peeling potatoes at a French restaurant called Chez François in the center of town. His father had left long ago, when Ed was two and his mother was pregnant with her third child. Jones’s sister, now fifteen, had moved up to Brooklyn a few years earlier to live with an aunt, and his sixteen-year-old brother was living in a “children’s village” in Laurel, Maryland, about twenty miles outside Washington. Jones vividly remembered the day his mother had to confront the reality that her middle child had come into the world with a brain that, as he would later put it, didn’t work quite right. Jones was four years old when a letter arrived. Unable to read or write, his mother had wandered through the boardinghouse where they lived, trying to find someone to read it. When she finally found a man on his way up the stairs, he told her that the note was from a city court, warning her that officials were coming to take Joseph away because he was “feeble-minded.” Jeanette had collapsed on the stairs in tears, clutching her daughter as Ed just watched and felt alone.

Now it was just Ed and his mother, living together but largely keeping out of each other’s way. He had turned off the evening news earlier than usual, thus missing the special bulletin that announced King’s assassination. Jones didn’t learn about King’s death until the next morning, when he turned on the radio. He and his mother sat in silence. Neither of them had ever paid much attention to the civil rights leader. His mother had been too busy keeping up with the demands of life to let herself get wrapped up in dreaming about civil rights. For her bookish son, the idea that King’s fight might become his own seemed equally remote.

By the time Jones went outside, he smelled smoke and stepped over broken glass—evidence of the rioting that had begun during the night. He was barely a block from home when a black man walked by, struggling with a television in his arms. A group of white men came up behind him and confiscated it. They looked official, wearing what appeared to be something akin to police uniforms, but there was something in the way they laughed when they grabbed the TV set that made Jones think they were just robbers in another guise.

Jones wandered the streets surveying the destruction. When he came up to a Hahn Shoes store he had passed every day, he stopped. The windows were broken and people were streaming onto the streets with as many shoe boxes as they could carry. Jones felt himself drawn inside, where his eyes watered from what he assumed must have been tear gas. His eyes fell on a display of twenty-dollar shoes, and he quickly pulled out a pair that seemed to be his size and ran out. They would be good shoes for college, he decided.

Although he performed well at school, Jones didn’t know much about his chances for college. He had looked at Howard University, but just applying there would have meant paying extra money to take the relatively new ACT college entrance exam in addition to the usual SAT test, so he had ruled it out. And he was nowhere near the top of the list at the new Federal City College, which seemed to be accepting everybody. He was no athlete, either. He hadn’t even done particularly well on the SAT. But a few months earlier, a young Jesuit who knew him from the neighborhood had told him about Holy Cross, where a priest named John Brooks was eager to recruit black students. The priest told Jones that Brooks might drive him to the campus for a weekend if Jones could get a bus to Philadelphia and meet up with some other students. Jones decided to follow up on the offer. As he grabbed the shoes, he was thinking about wearing them to Worcester.

Stanley Grayson was enjoying his status as a minor celebrity. The basketball team at All Saints High School in Detroit had recently won the state championships for the first time in its history, and many gave Grayson the credit. With just seconds left and a one-point lead in the final game, Grayson had been fouled and sank both his shots to seal a victory. The six-foot-four team captain was suddenly a hero. The city’s Catholic High School League named him outstanding scholar-athlete of the year. He was getting scholarship offers from schools that included Villanova and the University of Michigan. Having also helped his team finish as runner?up in the state championships the year before, Grayson didn’t have to worry about anyone doubting his skills. Whatever discomfort he may have felt at being black in a school full of Hungarian and Polish kids was outweighed by the reality that, at the moment, he was a star.

Grayson didn’t have many complaints. He couldn’t recall a time when he’d ever felt underprivileged. Detroit had been the site of a racial inferno a year earlier, but it wasn’t the same hotbed of inequality that characterized the South. The auto industry’s booming success enabled men of all colors to get assembly-line jobs, where they could make enough money to support their families. Grayson’s father, who worked in quality control at the Ford Motor Company, took pride in supporting his five children. He could be angry at times...

San Francisco Chronicle • The Plain Dealer

The inspiring true story of a group of young men whose lives were changed by a visionary mentor

On April 4, 1968, the death of Martin Luther King, Jr., shocked the nation. Later that month, the Reverend John Brooks, a professor of theology at the College of the Holy Cross who shared Dr. King’s dream of an integrated society, drove up and down the East Coast searching for African American high school students to recruit to the school, young men he felt had the potential to succeed if given an opportunity. Among the twenty students he had a hand in recruiting that year were Clarence Thomas, the future Supreme Court justice; Edward P. Jones, who would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize for literature; and Theodore Wells, who would become one of the nation’s most successful defense attorneys. Many of the others went on to become stars in their fields as well.

In Fraternity, Diane Brady follows five of the men through their college years. Not only did the future president of Holy Cross convince the young men to attend the school, he also obtained full scholarships to support them, and then mentored, defended, coached, and befriended them through an often challenging four years of college, pushing them to reach for goals that would sustain them as adults.

Would these young men have become the leaders they are today without Father Brooks’s involvement? Fraternity is a triumphant testament to the power of education and mentorship, and a compelling argument for the difference one person can make in the lives of others.

Les informations fournies dans la section « A propos du livre » peuvent faire référence à une autre édition de ce titre.

- ÉditeurSpiegel & Grau

- Date d'édition2012

- ISBN 10 0385524749

- ISBN 13 9780385524742

- ReliureRelié

- Nombre de pages242

- Evaluation vendeur

Acheter neuf

En savoir plus sur cette édition

Frais de port :

EUR 5

Vers Etats-Unis

Meilleurs résultats de recherche sur AbeBooks

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. In shrink wrap. N° de réf. du vendeur 100-02610

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Brand New Copy. N° de réf. du vendeur BBB_new0385524749

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. Buy for Great customer experience. N° de réf. du vendeur GoldenDragon0385524749

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. N° de réf. du vendeur Wizard0385524749

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Etat : new. N° de réf. du vendeur FrontCover0385524749

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New Copy. Customer Service Guaranteed. N° de réf. du vendeur think0385524749

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : new. New. Fast Shipping and good customer service. N° de réf. du vendeur Holz_New_0385524749

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Etat : New. Buy with confidence! Book is in new, never-used condition 1.2. N° de réf. du vendeur bk0385524749xvz189zvxnew

Fraternity: In 1968, a visionary priest recruited 20 black men to the College of the Holy Cross and changed their lives and the course of history.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : New. N° de réf. du vendeur Abebooks89770

Fraternity: In 1968, a Visionary Priest Recruited 20 Black Men to the College of the Holy Cross and Changed Their Lives and the Course of History.

Description du livre Hardcover. Etat : Brand New. 256 pages. 9.50x6.50x1.00 inches. In Stock. N° de réf. du vendeur 0385524749